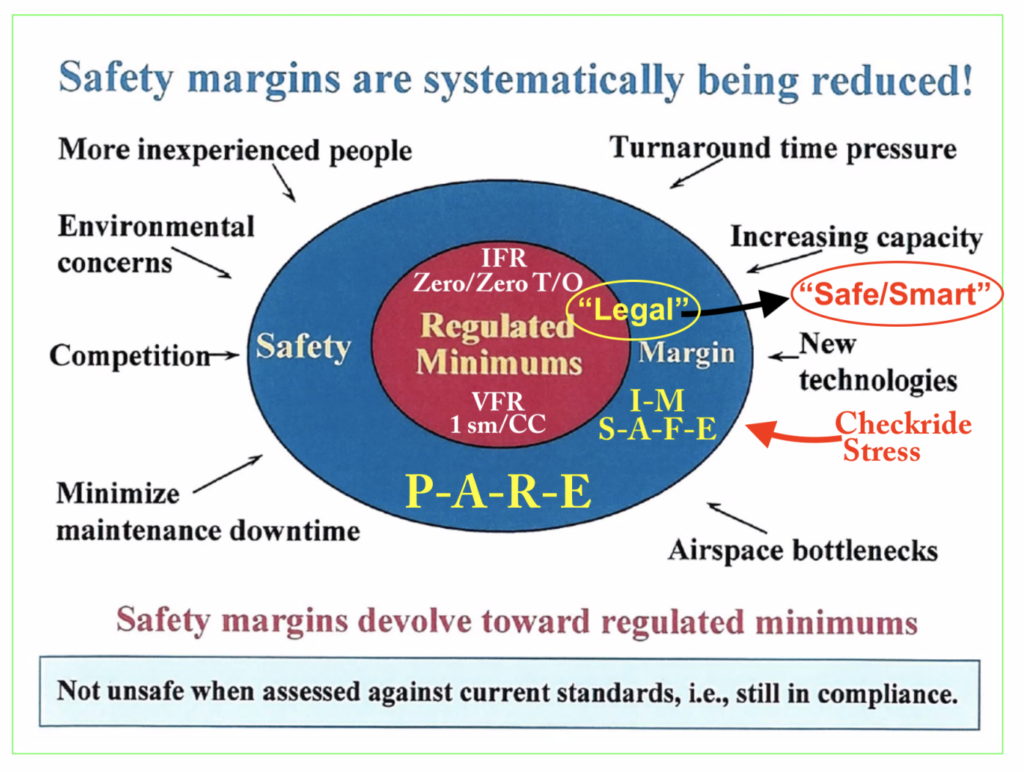

The whole ACS training/testing system is built on creating (and maintaining) a safety margin between what is “FAA legal” and what is “safe and smart” in flight. If you want to pass your FAA practical test—and subsequently stay alive as a pilot—understanding and internalizing this paradigm in all operations is essential. Pilots who advocate for “FAA minimums as an operating standard” scare me to death. We live with a “safety margin.” In the red zone, on the edge of “FAA legal,” a pilot is already in very dangerous territory. The FAA, under Part 91, only specifies absolute minimums. Maintaining a safety margin is essential for safety.

The “Pilot-Aircraft-enVironment-External pressure” or PAVE acronym, defines and maintains this safety margin. The dimensions depend on many personal factors, such as experience, skill, recent training, familiarity, etc. And precisely because these standards are personal, the defining line can get fuzzy. What is critical is defining the starting limits and maintaining these throughout flight. Every specific planned flight will require some modification. But the safety margin in blue (shown below) must be immutable for safety.

To understand the FAA regulatory philosophy, we first need to examine the FAA minimums for flying under CFR 14 Part 91. For daytime flying in Class G (“go for it”) airspace, the FAA only requires 1 statute mile of visibility and “clear of clouds.” This is legal, but may turn into a disaster unless you are over a familiar landscape in a slow airplane. Under all of Part 91, the FAA only specifies minimums. By contrast, the FAA strictly regulates flight under Parts 135 and 121.

Pilot Vs Aircraft

What is often misunderstood in the P-A-V-E acronym is the interactivity between the risk factors. A great pilot, with no knowledge of the specific airplane or environment, is obviously dangerous. One of my first “learners” as a new CFI was an Air Force General (and combat veteran) with more than 3,500 hours in F-16s. My job was transitioning him into civilian flying in a Grumman Tiger. This is an example of an absolutely amazing pilot with limited recent experience in GA aircraft or the civilian system—a totally new world.

As a CFI, have you ever tried to transition an airline pilot back into a little GA plane? This can be scary (and dangerous) without extensive ground time and a clear plan of action. Airline pilots only perform a small percentage of the piloting tasks required of a GA pilot; they are part of a larger team that performs those tasks (and the GA environment is much more challenging and unpredictable). Dispatch, maintenance, and weather analysis are handled by a team of specialists. This knowledge and skill need to be rebuilt for GA safety. And the landing height and energy management of a light aircraft, with limited technical assistance, will feel alien as well. They may be great pilots, but with a new plane, and a new environment.

Pilot and Aircraft Vs Environment

As we deal with winter weather ops in much of Northern America this time of year, the “Environment” area needs careful attention. Even the most capable GA piston airplane is vulnerable without FIKI certification. The FAA has stepped up with some very good training on winter ops to assist us. You may also want to check out some of these historic articles and a winter weather focus in the FAA Safety Briefing Magazine, which are also useful.

Fly safely out there, and often!